Digital Humanities

DH2010

King's College London, 3rd - 6th July 2010

Does Size Matter? Authorship Attribution, Small Samples, Big Problem

See Abstract in PDF, XML, or in the Programme

Eder, Maciej

Pedagogical University, Krakow, Poland

maciej_eder@poczta.onet.pl

The aim of this study is to find a minimal size of text samples for authorship attribution that would provide stable results independent of random noise. A few controlled tests for different sample lengths, languages and genres are discussed and compared. Although I focus on Delta methodology, the results are valid for many other multidimensional methods relying on word frequencies and "nearest neighbor" classifications.

In the field of stylometry, and especially in authorship attribution, the reliability of the obtained results becomes even more essential than the results themselves: failed attribution is much better than false attribution (cf. Love, 2002). However, while dozens of outstanding papers deal with increasing the effectiveness of current stylometric methods, the problem of their reliability remains somehow underestimated. Especially, the simple yet fundamental question of the shortest acceptable sample length for reliable attribution has not been discussed convincingly.

In many attribution studies based on short samples, despite their well-established hypotheses, convincing choice of style-markers, advanced statistics applied and brilliant results presented, one cannot avoid a very simple yet uneasy question: whether those impressive results could be obtained by chance, or at least positively affected by randomness? This question can be also formulated in a different way: if a cross-checking experiment with numerous short samples were available, would the results be just as satisfying?

Hypothesis

It is commonly known that word frequencies in a corpus are random variables; the same can be said about any written authorial text, like a novel or poem. Being a probabilistic phenomenon, word frequency strongly depends on the size of the population (i.e. the size of the text used in the study). Now, if the observed frequency of a single word exhibits too much variation for establishing an index of vocabulary richness resistant to sample length (cf. Tweedie and Baayen, 1998), a multidimensional approach – based on several probabilistic word frequencies – should be even more questionable.

On theoretical grounds, we can intuitively assume that the smallest acceptable sample length would be hundreds rather than dozens of words. Next, we can expect that, in a series of controlled authorship experiments with longer and longer samples tested, the probability of attribution success would at first increase very quickly, indicating a strong correlation with the current text size; but then, above a certain value, further increase of input sample size would not affect the effectiveness of the attribution. In any attempt to find this critical point in terms of statistical investigation, one should be aware, however, that this point might depend – to some extent – on the language, genre, or even the text analyzed.

Experiment I: Words

A few corpora of known authorship were prepared for different languages and genres: for English, Polish, German, Hungarian, and French novels, for English epic poetry, Latin poetry (Ancient and Modern), Latin prose (non-fiction), and for Ancient Greek epic poetry; each contained a similar number of texts to be attributed. The research procedure was as follows. For each text in a given corpus, 500 randomly chosen single words were concatenated into a new sample. These new samples were analyzed using the classical Delta method as developed by Burrows (2002); the percentage of attributive success was regarded as a measure of effectiveness of the current sample length. The same steps of excerpting new samples from the original texts, followed by the stage of "guessing" the correct authors, were repeated for the length of 600, 700, 800, ..., 20000 words per sample.

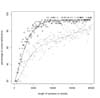

The results for a corpus of 63 English novels are shown on Fig. 1. The observed scores (black points on the graph; grey points will be discussed below) clearly indicate the existence of a trend (solid line): the curve, climbing up very quickly, tends to stabilize at a certain point, which indicates the minimal sample size for the best attributing rate. It becomes quite obvious that samples shorter than 5000 words provide a poor "guessing", because they can be immensely affected by random noise. Below the size of 3000 words, the obtained results are simply disastrous. Other analyzed corpora showed that the critical point of attributive success could be found between 5000 and 10000 words per sample (and there was no significant difference between inflected and non-inflected languages). Better scores were obtained for the two poetic corpora: English and Latin (3500 words per sample were enough for good results), and, surprisingly, the corpus of Latin prose (its minimal effective sample size was of some 2500 words; cf. Fig. 2, black points).

Experiment II: Passages

The way of preparing samples by extracting a mass of single words from the original texts seems to be an obvious solution for the problem of statistical representativeness. In most attribution studies, however, shorter or longer passages of disputed works are usually analyzed (either randomly chosen from the entire text, or simply truncated to the desired size). The purpose of the current experiment was to test the attribution effectiveness of this typical sampling. The whole procedure was repeated step by step as in the previous test, but now, instead of collecting individual words, sequences of 500 words (then 600, 700, ..., 20000) were excerpted randomly from the original texts.

Three main observations could be made here: 1. For each corpus analyzed, the effectiveness of such samples (excerpted passages) was always worse than the scores described in the former experiment, relying on the "bag-of-words" type of sample (cf. Fig. 1 and 2, grey points). 2. The more inflected the language, the smaller the difference in correct attribution between both types of samples, the "passages" and the "words": the greatest in the English novels (cf. Fig. 1, grey points vs. black), the smallest in the Hungarian corpus. 3. For "passages", the dispersion of the observed scores was always wider than for "words", indicating the possible significance of the influence of random noise. This effect might be due to the obvious differences in word distribution between narrative and dialogue parts in novels (cf. Hoover, 2001); however, the same effect was equally strong for poetry (Latin and English) and non-literary prose (Latin).

Experiment III: Chunks

At times we encounter an attribution problem where extant works by a disputed author are doubtless too short for being analyzed in separate samples. The question is, then, if a concatenated collection of short poems, epigrams, sonnets, etc. in one sample (cf. Eder and Rybicki, 2009) would reach the effectiveness comparable to that presented above? And, if concatenated samples are suitable for attribution tests, do we need to worry about the size of the original texts constituting the joint sample?

The third experiment, then, was designed as follows. In 12 iterations, several word-chunks were randomly selected from each text into 8192-word samples: 4096 bi-grams, 2048 tetra-grams, 1024 chunks of 8 words in length, 512 of 16 words, and so on, up to 2 chunks of 4096 words. Thus, all the samples in question were 8192 words long. The obtained results were very similar for all the languages and genres tested. As shown in Fig. 3 (for the corpus of Polish novels), the effectiveness of "guessing" depends to some extent on the word-chunk size used. Although the attributive scores are slightly worse for long chunks within a sample (4096 words or so) than for bi-grams, 4-word chunks etc., every chunk size could be acceptable to constitute a concatenated sample.

However, although this seems to be an optimistic result, we should remember that this test would not be feasible on really short poems. Epigrams, sonnets etc. are often masterpieces of concise language, with a domination of verbs over adjectives and so on, and with a strong tendency to compression of content. For that reason, further investigation is needed here.

Conclusions

The scores presented in this study, as obtained with classical Delta procedure, would be slightly better when solved with Delta Prime, and worse if either Cluster Analysis or Multidimensional Scaling is used (a few tests have been done). However, the shape of all the curves, as well as the point where the attributive success rate becomes stable, are quite identical for each of these methods. The same refers to different combinations of style-markers' settings, like "culling", the number of the Most Frequent Words analyzed, deleting/non-deleting pronouns, etc. – although different settings provide different "guessing" (up to 100% for the most efficient), they never affect the shape of the curves. Thus, since the obtained results are method-independent, this leads us to a conclusion about the smallest acceptable sample size for future attribution experiments and other investigations in the field of stylometry. It also means that some of the recent attribution studies should be at least re-considered. Until we develop style-markers more precise than word frequencies, we should be aware of some limits in our current approaches. As I tried to show, using 2500-word samples will hardly provide a reliable result, to say nothing of shorter texts.

References

- Burrows, J. F. (2002). 'Delta: a Measure of Stylistic Difference and a Guide to Likely Authorship'. Literary and Linguistic Computing. 17: 267-287

- Craig, H. (2004). 'Stylistic Analysis and Authorship Studies'. A Companion to Digital Humanities. S. Schreibman, R. Siemens and J. Unsworth (ed.). Blackwell Publishing, pp. 273-288

- Eder, M., Rybicki, J. (2009). 'PCA, Delta, JGAAP and Polish Poetry of the 16th and the 17th Centuries: Who Wrote the Dirty Stuff?'. Digital Humanities 2009: Conference Abstracts. University of Maryland, College Park, pp. 242-244

- Hoover, D. L. (2001). 'Statistical Stylistic and Authorship Attribution: an Empirical Investigation'. Literary and Linguistic Computing. 16: 421-444

- Hoover, D. L. (2003). 'Multivariate Analysis and the Study of Style Variation'. Literary and Linguistic Computing. 18: 341-360

- Juola, P., Baayen R. H. (2005). 'A Controlled-corpus Experiment in Authorship Identification by Cross-entropy'. Literary and Linguistic Computing. Suppl. Issue 20: 59-67

- Love, H. (2002). Attributing Authorship: An Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- Rudman, J. (1998). 'The State of Authorship Attribution Studies: Some Problems and Solutions'. Computers and the Humanities. 31: 351-365

- Rybicki, J. (2008). 'Does Size Matter? A Re-examination of a Time-proven Method'. Digital Humanities 2008: Book of Abstracts. University of Oulu, pp. 184

- Tweedie, J. F. and Baayen, R. H. (1998). 'How Variable May a Constant be? Measures of Lexical Richness in Perspective'. Computers and the Humanities. 32: 323-352

© 2010 Centre for Computing in the Humanities

Last Updated: 30-06-2010