Digital Humanities

DH2010

King's College London, 3rd - 6th July 2010

Critical Editing of Music in the Digital Medium: an Experiment in MEI

See Abstract in PDF, XML, or in the Programme

Viglianti, Raffaele

King's College London UK

raffaele.viglianti@kcl.ac.uk

Critical editions of music have not received the level of attention that research in Digital Humanities has given to textual criticism, which already has an established scholarly production of written contributions and digital publications. Digital representations in literary criticism are used for analytical purposes as well as for accommodating critical editions in the digital medium, which offers a high degree of interactivity and opens toward experimentation with new formats of publication. Nonetheless, there has been little debate about music editing in the new medium and only a few digital publications have been developed.

Several aspects of digital textual criticism can find an application on music documents because similar issues exist in the representation of primary sources and editorial intervention. In fact, since the early stages of music scholarship, musicologists looked at the editorial practices of classical philologists while working towards a definition of their own scientific finalities (Grier, 1996). The study of documentary sources transmitting a written work (manuscript or printed) is the main correlation between music and textual criticism. For instance, the discrepancy identified by Tanselle (1989) between text and the artefacts that transmit it, is a condition that applies to music notation as well as literature; however, literature is ‘a one-stage and music a two-stage art’ (Goodman, 1976:114; also discussed by Feder, 1987). A musical work, in fact, does not exist only as written notation but also requires performance to reach its final receiver. For this reason, understanding the complexity of the music work-concept and its associated cultural practices is central to the digital representation of music critical editions. Even though the recent research in digital textual scholarship provides a rich paradigm for the emergent field of digital editing of music, there is the need for more research on digital representation and publication of detailed notation data.

The work conducted for a postgraduate dissertation (MA) at King’s College London attempted to discuss some of these issues. This poster presents the results of the dissertation’s case study: a digital edition of Claude Debussy’s Syrinx (La Flûte de Pan) for flute solo. The XML-based model represents notation, variant readings and editorial intervention; additionally, several different views are extracted and rendered for presentation with vector images.

An experiment with MEI: Syrinx (La Flûte de Pan) by Claude Debussy

Syrinx (La Flûte de Pan) by Claude Debussy (1862 – 1918) is a short piece for flute solo originally composed as theatrical interlude for the play Psyché (1913) by Gabriel Mourey under the title La Flûte de Pan. Despite Debussy showing little interest in the publication of the piece, the first performer, Louis Fleury, contributed to the reception of the piece as independent from Mourey’s play. The piece maintains a relevant role in the solo flute repertoire. Two principal sources have been used for the digital edition: the first edition published posthumously by Jobert in 1927 under the new title Syrinx and a recently discovered manuscript in a private collection in Brussels dated 1913 (MSB), which constituted the base text.

For the creation of a digital model for the new edition, the use of a combination of TEI and MusicXML was initially considered;1 however, MusicXML does not match TEI’s flexibility when encoding primary sources and variant readings. MusicXML, in fact, is primarily designed ‘to be sufficient, not optimal’ (Good, 2001); therefore, it represents normalised common western music notation to facilitate interchange and does not allow the flexibility in the granularity that is required when representing the editor’s interpretation and understanding.

The Music Encoding Initiative (MEI) provided an alternative choice.2 This XML format is modelled on TEI and attempts to follow the same principles. In particular it specifically focuses on formalising interpretation through declarative knowledge and claims to be independent from rendering software while also addressing processing matters (Roland, 2002).3 Moreover, it includes a module for the representation of variant readings and transcription of primary sources; therefore a combination with TEI did not seem to be necessary. The MEI format is still in development; however, the University of Paderborn (Germany) and the University of Virginia (USA) recently received a grant to take MEI out of its beta phase and produce public guidelines, which should be completed by the end of July 2010.4

The encoding model

The poster will show how the MEI model represents some editorial aspects common with textual editing (i.e. bibliographical metadata, correction and regularisation) and editorial issues related to the nature of the music notation (i.e. apparatus, rhythmic constraints, performative instructions). In particular it will show:

- The header: similarly to TEI, MEI provides a

“header” (<meihead>) that allows documenting information about the

digital file and its sources. Notably, the elements in the description

of the manuscript source MSB attempt to emulate the much more detailed

encoding model offered by the TEI manuscript description module. The

header also documents the encoding criteria for notation.

<measure> <staff> <layer> //- Notes <note>, <beam>, <tuplet>, etc. ... </layer> //- Phrase marks <slur> ... //- Dynamics, tempo markings and directions positioned above the staff <dir>, <dynam>, <breath>, etc. ... //- Dynamics, tempo markings and directions positioned below the staff <dir>, <dynam>, <breath>, etc. ... </staff> </measure> - Variant readings: The MEI file represents this

edition’s base text (MSB) and adds additional information every time a

difference in the other sources occurs. If the sources agree, it is

expressed silently. This criterion is identified by the TEI guidelines

as ‘internal parallel segmentation’.5

Example 2 shows alternative notations encoded with <app> and

<rdg>; the attribute type specifies which reading has been

selected for the edition. It is worth explaining the basic mechanisms

behind the element <slur>, since they are also common to other

elements. The attribute staff defines to which staff the phrase mark

belongs to; place defines whether the slur has to be rendered above or

below the staff; tstamp identifies the beat in which the slur starts and

dur the beat in which the slur ends.

<measure id="m28" n="28"> ... <app> <rdg source="MSB"> <slur staff="1" tstamp="2" dur="4" place="above"/> </rdg> <rdg source="FEJ" type="ed"> <slur staff="1" tstamp="2" dur="2.875" place="above"/> <slur staff="1" tstamp="3" dur="3.75" place="above"/> </rdg> </app> ... </measure> - Editorial conjecture and intervention: change of hand, additions, corrections and supplied notation have been encoded with elements equivalent to the ones employed by the TEI.

- Problematic cases: bar 22 in MSB presents an incongruent rhythm and a missing barline to separate it from bar 23. The encoding used an empty-element version of <beam> to encode the differences in beaming resulting from the different rhythms and a <gap> element for the missing barlines.

Presentation

For this edition, a number of different perspectives from the MEI document are produces using XSLT 2.0 to serialize into a text format for Mup, a program that converts its own notation format into Post Script vector graphics (PS). To extract musical information from the encoded edition, a heavily customised version of a MEI to Mup XSLT provided on the MEI website under the Educational Community Licence. The poster will show the following views:

- The edited piece. The XSLT script extracts all the variant readings chosen for the edition, includes the editorial interventions marked with <supplied> and creates a new MEI document tree containing only the notation for the edition. This tree is then serialised into Mup language and rendered in PS.

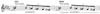

- Synoptic apparatus. Instead of printing a traditional apparatus, this edition proposes a synoptic apparatus of the two main sources (MSB and FEJ). This is automatically built to display measures that contain variant readings. Moreover, it has been programmed to display the notation of the two sources in a semi-diplomatic manner and excluding editorial intervention.

- Breath marks. MSB has fewer breath marks than the first edition FEJ and it is possible that Debussy did not provide all the breath marks necessary for performance. Trevor Wye (1994), in his edition of Syrinx, introduces a number of recommended breath marks to support the performance. Since Wye employs MSB as a base text, his breath marks are suitable for this edition’s notation as well. The encoding for this case study edition includes Wye’s additions with the element <add resp="Wye">. The XSLT programmed to transform the edited music notation can, if requested, include these marks in the Mup output.

Future work

The views created for this prototype are static; however it would be highly desirable to combine them in an interactive environment. For example, the apparatus could be enhanced allowing moving measures on the screen to be compared. Performers might be interested in knowing different tempi and breath marks from other editions, like Wye’s breath marks, and include them in the edition to be printed out with a printing device at home. Paper editions with a similar approach are not uncommon, but often include comparative tables of tempi and resolution of ornaments that cannot be directly included in the edited text (see Palmer, 1991).

Even though the Web is currently the preferred digital publishing environment, there still is not a straightforward method to output notation as HTML and possibly there will never be. The only possibility to publish music on the Web is through graphic information; however, systems for delivering complex interactivity based on image formats are becoming increasingly common. OpenLayers, for example, shows how images can be made highly interactive through the superimposition of layers.6 Future work will focus on implementing interactivity on the PS views in OpenLayers.

References

N.B. All websites mentioned in footnotes have been accessed 6 March 2010.

- Bach, Johann S. (1991). Inventions and Sinfonias (Two- and Three-Part Inventions). Palmer, W. A. (ed.). Van Nuys (CA, USA): Alfred Publishing

- Debussy, Claude (1927). Syrinx. Paris: Jobert

- Debussy, Claude (1991). La Flûte de Pan. Ljungar-Chapelon, A. (ed.). Malmö: Autographus Musicus, Facsimile

- Debussy, Claude (1996). Syrinx (La Flûte de Pan). Stegemann, M. and Ljungar-Chapelon, A. (eds.). Wien: Wiener Urtext Edition

- Feder, Georg (1987). Musikphilologie: eine Einführung in die musikalische Textkritik, Hermeneutik und Editionstechnik. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft

- Grier, James (1996). The Critical Editing of Music: History, Method, and Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- Good, M. (2001). 'MusicXML for Notaiton and Analysis'. Computing in Musicology. 12: 113-124

- Goodman, Nelson (1976). Languages of art: an approach to a theory of symbols. Chicago: University of Chicago Press

- Roland, P. (2002). The Music Encoding Initiative (MEI). http://www2.lib.virginia.edu/innovation/mei/Papers/maxpaper.pdf (accessed 6 March 2010)

- Sperberg-McQueen, C. M. (2009). 'How to teach your edition how to swim'. Literary & Linguistic Computing. V. 27-39. 24.1

- Tanselle, G. Thomas (1989). A rationale of textual criticism. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press

Footnotes

- 1.

- MusicXML (distributed with a royalty-free license) is an interchange format developed by Recordare LLC (http://www.recordare.com). It is employed by free and commercial music editors (i.e. Finale and Sibelius) as intermediate representation to exchange data (often with loss). Back to context...

- 2.

- http://www2.lib.virginia.edu/innovation/mei/ Back to context...

- 3.

- This approach recalls the claim of Sperberg-McQueen (1997) that ‘declarative’ information about the editorial process can be represented and modelled through markup: ‘there is an infinite set of facts related to the work being edited’ and ‘any edition records a selection from the observable and the recoverable portions of this infinite set of facts’. This selection represents what the edition ‘knows […] about the work edited, its genesis and/or transmission, etc.’. This body of information is ‘declarative’. Back to context...

- 4.

- http://www2.lib.virginia.edu/press/music/index.html Back to context...

- 5.

- http://www.tei-c.org/release/doc/tei-p5-doc/en/html/TC.html#TCAPPS Back to context...

- 6.

- http://openlayers.org/ Back to context...

© 2010 Centre for Computing in the Humanities

Last Updated: 30-06-2010